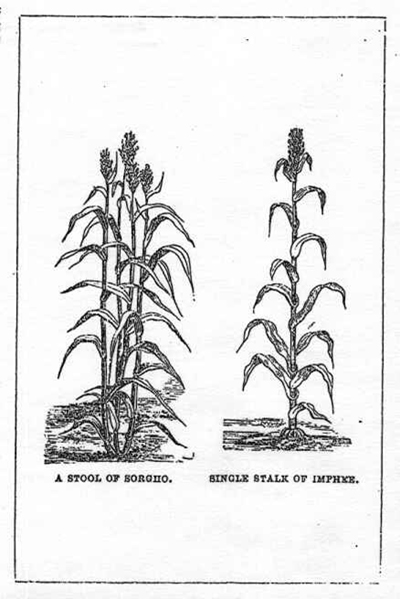

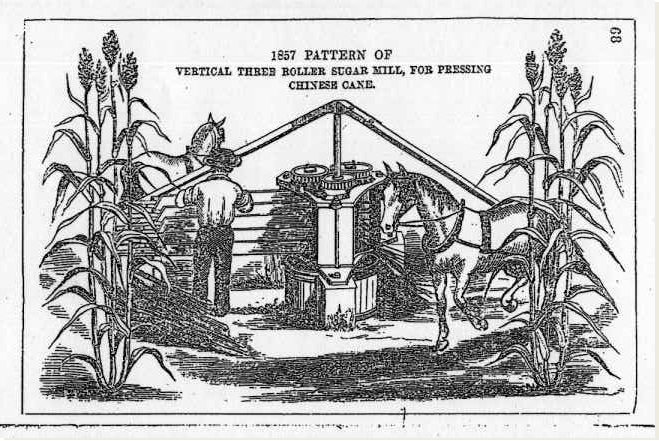

An 1859 book, “Experiments with Sorghum Sugar Cane”, was written to encourage the northern farmer to think they could be sugar independent almost immediately. Here are some interesting quotes from that “inspiring” little book, “The profound interest awakened, not many months since, on the subject of the introduction among us of a new sugar producing plant, the Chinese Sorgho and African Imphee canes, seems destined to ripple yet further the current public sentiment. No event of modern times has produced a sensation more intense amongst agriculturists, and judging from the success which has attended the experiments of the past season, crude and imperfect as they necessarily were, nothing has fallen under public observation which has yet, or is likely to confer such permanent benefit upon the community at large.

Sugar, once a rare and costly luxury, has in these latter times become a sort of general necessity, although the short crops of year or two past, together with inordinate speculations in that which was produced, have made men of moderate and restricted means feel as if it was receding again to its old place amongst the luxuries.

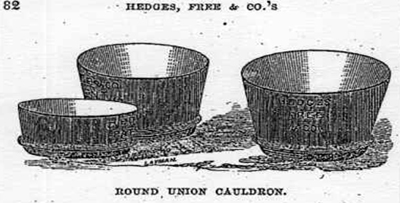

Our object here, however, is not to indulge in general speculation, but to lay before the public, in the plainest manner possible, such facts as have fallen under our observation, or have been brought to our attention, and which bear upon the subject of growing this new sugar cane, expressing the juice there from, and boiling the same into sugar and molasses, We will therefore as a proper preface, consider the general success of the past season, to show the base upon which we build our hopes of still more flattering results in the future."

The results of the year are flattering in the highest degree. Sirup, of a beauty and flavor and consistency equal to the finest sugar house molasses, has been made to a considerable extent in nearly every Northern State, and in quantity sufficient yield a good profit at the lowest price New Orleans has ever sold for in our markets. Samples have been shown us by various parties, which were as transparent and pleasant almost as honey, though there had, doubtless been unusual care exercised in their manufacture. They show, however, that these results were not impossibilities, and go far to prove the cane a success. But, in addition, to all this, and still better, SUGAR, of various grades, from the darkest brown to the finest loaf, has been produced by various parties and at various points, sufficient to prove conclusively that the manufacture of sugar in this latitude is not only possible, but easy of accomplishment."

With a bag of free sweet sorghum seeds from the US patent office, a copy of this book, and a small amount of equipment, the 1850′s northern farmer has sugar stars in his or her eyes. No more trips to the general store to buy expensive slave made cane sugar. This appealed to the cost conscious early American and worked for US government too.

But, there was still another factor. Self reliance was a core value amongst the American pioneer. They liked being able to take care of their own and produce their own necessities. Part of this was practical; many lived in locations far removed from a general store. But, the bigger part was the value of self reliance itself. They liked being able to fend for themselves. Making their own sugar made them more independent.

For all these reasons, sweet sorghum planting, and sorghum syrup manufacture, throughout the North, caught on like wild fire.

Though the US patent office had sowed the seeds of northern sugar independence, and authors such as the one just quoted helped stir the so called sugar pot, the Civil War did its part to stimulate northern sugar production. Let’s just say the war, which specifically targeted sugar plantations, resulted in a disruption in the production and distribution of southern cane sugar. As the war raged on, the sugar flow slowed to a trickle. The northern states did not have access to southern sugar they had before. If you wanted to get your sweet on , planting and producing sorghum syrup was the answer.

At that crazy time in US history, an Iowa agriculturist, Wayne Rasmussen, made this statement, “It is fair to conclude that if a king providence should bless us with a favourable season, another year we will not be compelled, as a State, to contribute to the expenses of the war in the shape of high prices for sugar and molasses.” In other words, northern sugar production meant less money for the south to fight their side of the civil war.

Though the US patent office had sowed the seeds of northern sugar independence, and authors such as the one just quoted helped stir the so called sugar pot, the Civil War did its part to stimulate northern sugar production. Let’s just say the war, which specifically targeted sugar plantations, resulted in a disruption in the production and distribution of southern cane sugar. As the war raged on, the sugar flow slowed to a trickle. The northern states did not have access to southern sugar they had before. If you wanted to get your sweet on , planting and producing sorghum syrup was the answer.

At that crazy time in US history, an Iowa agriculturist, Wayne Rasmussen, made this statement, “It is fair to conclude that if a king providence should bless us with a favourable season, another year we will not be compelled, as a State, to contribute to the expenses of the war in the shape of high prices for sugar and molasses.” In other words, northern sugar production meant less money for the south to fight their side of the civil war.

The Union Commissioner of Agriculture said this in his report of 1862, “The new product of sorghum cane has established itself as one of the permanent crops of the country and it enabled the interior states to supply themselves with a home article of molasses, thereby keeping down the prices of other molasses from any great advance over former rates which otherwise would have been a result of war.” The sugar shortage, that would otherwise have been the practical result of war with the south, was averted with northern sorghum syrup production . Northern farmers were now making their own sugar and had their own supply. And, often, they had enough to sell to their neighbors and city dwellers.

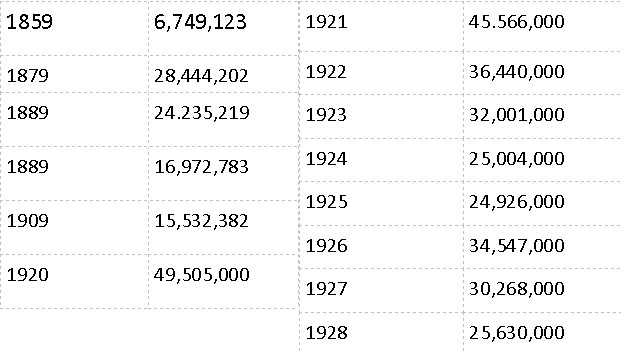

Sorghum production increased with each passing year of the war. However, its production stabilized in the 1870′s. Basically, with the end of the war, and with the renewed access to southern sugar, Sorghum had to stand toe to toe with southern cane sugar. Though Sorghum got northern folks through the war years, it was not without its problems. In the very northern states it did not always set seed. Where ever it was planted, it was labor intensive to convert the cane into sugar syrup. However thrifty, making sugar was time consuming, and if you had money to buy sugar, you did.

So, 1870′s saw a reduction of sorghum production in the north, but as production in the north declined, it increased in the northern parts of the south. The parts that were too cold for sugar cane to grow, but, still plenty warm for sorghum. This increase in southern sorghum syrup production might also have had something to do with labor. Though slavery was over, the south had a large number of former slaves accustomed to labor intensive agriculture, cotton, cane, and tobacco included, in need of work. Though freed, former slaves were available for the manual labor associated with making sorghum syrup.

As has been said, there are different sorghum varieties grown for different purposes, silage, grain, broom, and sugar respectively. Apparently the US Department of Agriculture decided this confused the American consumer. In one of the earliest cases of re-branding by the USDA, the USDA announced that hence forth, sweet sorghum would be called Sorgo and sorghum syrup would be called sorgo syrup.

Here is a humorous quote from one of their publications announcing “their” name change,“Sorgo is called sorghum in many parts of the country, and until recently the sirup from sorgo was generally known as sorghum syrup. Sorgo is the name now preferred by the United States Department of Agriculture for the varieties of sorghum that have abundant sweet juice, as distinguished from the grain producing varieties”. Sadly for the USDA, no one was interested in changing sorghum syrups name, and, their effort failed. Then and now, sorghum syrup is called sorghum syrup and sometimes just plain old sorghum.

Sorghum syrup production reached one its peak in the 1880′s where states, southern and northern included, produced a total of 30 million gallons of syrup. At this time, there were over two hundred different varieties of sorghum planted in North America. Each location tended to have its own variety that performed best in that locale.