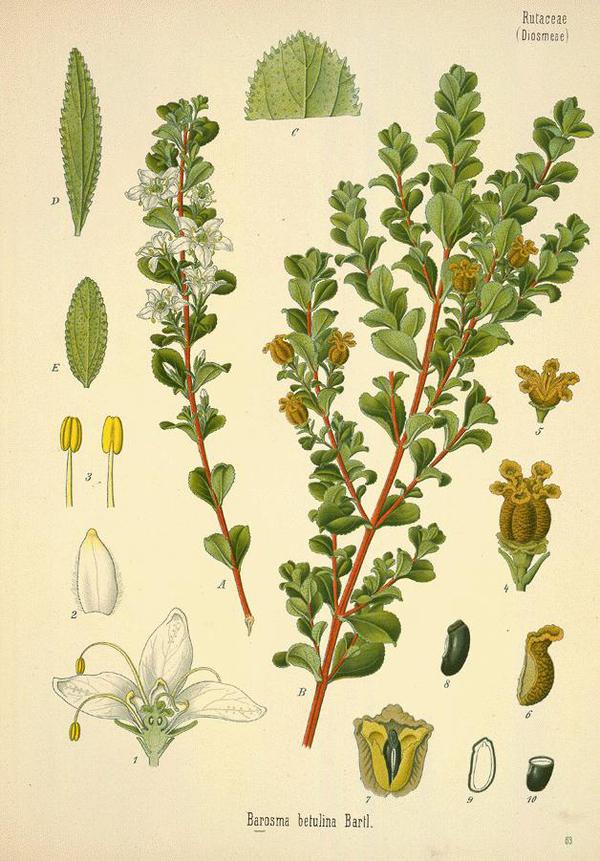

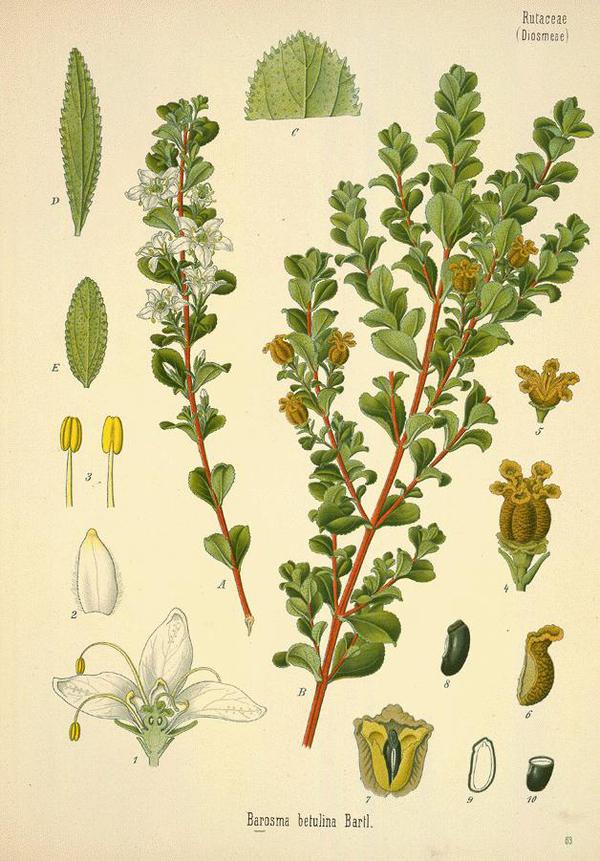

Common Name: Buchu | Scientific Name: Barosma Betulina

Resources

Fact Sheet

Notes from the Eclectic Physicians

Fact Sheet

In a word: Urinary tract infection miracle plant

Uses: Contains oils that kill bacteria hanging out in the urinary tract: urethritis and cystitis

Buchu is a curious herbal medicine. It smells like black currants and has the unglamorous attribute of being able to clear up urinary tract infections! It was first used by the tribes in South Africa as a general tonic and specifically for urinary tract infections. In time the South African Colonials came to know it and they too used it for general health purposes and in urinary tract infections. To this day, it is one of herbalists favourites when urinary tract infections are causing a problem.

History

In 1909 Felter and Lloyd had this to say of Buchu: “The plants yielding buchu are indigenous to Southern Africa, occupying a limited extent of territory. According to Burchell they are odoriferous, and are, when powdered, used by the Hottentots under the bame of Bookoo or Buku, for anointing their bodies. They likewise prepare a buchu brandy by distilling the leaves with wine, and which they employ as an efficient remedy in all affections of the stomach, bowels, and bladder; they also apply a decoction of the leaves to wounds. Buchu is said to have been introduced into medicine by a London drug firm (Reece & Co., in 1821), to whom a supply had been sent by Cape Colonists, who learned its uses from the Hottentots. “

Dr. King tells us a little more about its uses in American medical circles at the beginning of this century.

“Buchu is a stimulant, diuretic, antispasmodic, and tonic. Useful in all diseases of the urinary organs attended with increased uric acid; in irritation of the bladder and urethra attending gravel, in catarrh of the urinary bladder, and incontinence connected with diseased prostate. It has also been recommended in dyspepsia, dropsy, cutaneous affections, and chronic rheumatism.”

Urinary tract infections have always been a problem for the medical profession and this was the case in the last century. When buchu became known it was instantly popular because it very quickly cleared a urinary tract infection. In fact, it was so popular it became a highly sought after commodity. Lloyd said this of the herbal medicine in 1911, Reece and Company, London, 1821, first imported it and introduced it to pharmacy and to the medical profession, where, as well as in private formulae and domestic practice, it has ever since enjoyed more or less notoriety. Perhaps no “patent” American medicine has every enjoyed greater notoriety than about 1860, did the decoction of the leaves under the term “Hembold’s Buchu.” which, a weak alcoholic decoction, commanded one dollar for a six-ounce vial, and sold in car-load lots. During the crusade of this preparation the medical profession of America, probably inspired by the press comments, prescribed buchu very freely. It is still in demand and is still favoured as a constituent of remedies recommended to the laity.”

Science

One of the nice things about buchu is that it is pleasant to taste. Unlike some herbal remedies, Buchu is a pleasure to use. The oils that give buchu its very pleasing black currant taste are also responsible for its ability to kill bacteria in the urinary tract. The oils are absorbed by the stomach and excreted by the kidneys into the bladder. As the oils pass through the bladder and urethra, they kill bacteria as they go. Science has revealed that Buchu is a urinary tract disinfectant of the truest sort.

Practitioners’ Advice

The issue with urinary tract infections is that they tend to be chronic in nature. One urinary tract infection clears just in time for another urinary tract infection to begin. This is not a coincidence. The first infection weakens the urinary tract and makes it easier for bacteria to move in and cause the second urinary tract infection. The third infection makes it even easier for the fourth and so on. One urinary tract infection makes the urinary tract vulnerable to infection. The term sitting duck comes to mind. It is important to interrupt the cycle of urinary tract infections. Many herbalists use a two-pronged approach to accomplish this. Firstly, they advocate the use of an immune stimulant like Echinacea or Maitake. A fired up immune system is much better able to police the urinary tract for bacteria and kill them if they run into any. So the first thing to do is to get the immune system marching double time in a war against bacteria. The second thing to do is to regularly use bacteria killing Buchu. Every time you drink a cup of Buchu tea, bacteria killing oils pass through the urinary tract. As the oil passes through, it kills bacteria. This double whammy has effectively ended the cycle of urinary tract infections for more than one long time sufferer. By the by, Buchu sometimes gives the urine a distinct black currant scent! We would not like anyone to be caught unawares.

QUICK REVIEW

History: Traditional African urinary tonic

Science: Volatile oils kill bacteria and increase urinary output

Practitioners’ opinion: Should be used long term to clear infection

Notes from the Eclectic Physicians

1909: Felter and Lloyd: BUCHU (U.S.P.) – BUCHU

History – The plants yielding buchu are indigenous to Southern Africa , occupying a limited extent of territory. According to Burchell they are odoriferous, and are, when powdered, used by the Hottentots under the bame of Bookoo or Buku, for anointing their bodies. They likewise prepare a buchu brandy by distilling the leaves with wine, and which they employ as an efficient remedy in all affections of the stomach, bowels, and bladder; they also apply a decoction of the leaves to wounds. Buchu is said to have been introduced into medicine by a London drug firm (Reece & Co., in 1821), to whom a supply had been sent by Cape Colonists , who learned its uses from the Hottentots (Pharmacographia).

Buchu leaves have a strong odor, resembling somewhat that of pennyroyal, and a corresponding taste. When held up to the light translucent dots may be observed, owing to the fact that the under surface of the leaves is beset with scattered glandular oil-points. If buchu leaves be preserved with ordinary care, their odor will remain for some years. The long variety of buchu is occasionally adulterated with leaves of Empleurum serrulatum, Aiton (Rutacae), a shrub growing in the same locality with buchu. They have a different odor from buchu, a bitter taste, are narrower than buchu leaves, and the oil-gland at the apex, present in B. Serratifolia, is absent. Moreover, the adulterant has leaves with an acute apex, while those of long buchu are truncate. The leaves of another species of the same order, the B. Eckloniane, Berg, has also been imported with true buchu. They are markedly crenate, have a rounded base, and are grown on pubescent twigs (Pharmacographia).

1909: Felter and Lloyd: BUCHU (U.S.P.) – BUCHU

History – The plants yielding buchu are indigenous to Southern Africa , occupying a limited extent of territory. According to Burchell they are odoriferous, and are, when powdered, used by the Hottentots under the bame of Bookoo or Buku, for anointing their bodies. They likewise prepare a buchu brandy by distilling the leaves with wine, and which they employ as an efficient remedy in all affections of the stomach, bowels, and bladder; they also apply a decoction of the leaves to wounds. Buchu is said to have been introduced into medicine by a London drug firm (Reece & Co., in 1821), to whom a supply had been sent by Cape Colonists , who learned its uses from the Hottentots (Pharmacographia).

1911: LLoyd

The Hottentots of the Cape of Good Hope used the leaves of the Buchu plant (Barosma betulina) as a domestic remedy, and from them the colonists of the Cape of Good Hope derived their information concerning it. Reece (540) and Company, London , 1821, first imported it and introduced it to pharmacy and to the medical profession, where, as well as in private formulae and domestic practice, it has ever since enjoyed more or less noteriety. Perhaps no “patent” American medicine has every enjoyed greater notoriety than about 1860, did the decoction of the leaves under the term “Hembold’s Buchu.” which, a weak alcoholic decoction, commanded one dollar for a six-ounce vial, and sold in car-load lots. During the crusade of this preparation the medical profession of America , probably inspired by the press comments, prescribed buchu very freely. It is still in demand and is still favored as a constituent of remedies recommended to the laity.

1921: Lloyd

Mentioned first in 1840 under the name, “Diosma, Buchu.” In 1850 the name Buchu necame official, this title being still employed in the edition of 1910. Several varieties of Barosma are recognized in different editions of the U.S.P. as producing the official “Buchu” leaves. The 1910 edition names as official the leaves of Barosma betulina, (Short Buchu of commerce), and of Barosma serratifolia (Long Buchu).

The Hottentots of the Cape of Good Hope used the leaves of the buchu plant, Barosma Betulina, as a domestic remedy, and from them the colonists of the Cape of Good Hope derived their information concerning it. Reece (540) and Company, London, 1821, first imported buchu and introduced it to pharmacy and the medical profession, among whom it has since emjoyed more or less favor, as well as in private formulae and domestic practice. Perhaps no “patent” American medicine has ever enjoyed greater notoriety than, about 1860, did a weak decoction of the leaves under the term “Helmbold’2 Buchu”, which in six-ounce bottles was sold in quantities, even car-load lots, commanding the price of one dollar per bottle. During the crusade of this preparation by Helmbold, the medical profession of America , probably inspired by press comments, prescribed buchu very freely. Buchu is still in demand, and is still favored as a constituent of remedies recommended to the laity.

Disclaimer: The author makes no guarantees as to the the curative effect of any herb or tonic on this website, and no visitor should attempt to use any of the information herein provided as treatment for any illness, weakness, or disease without first consulting a physician or health care provider. Pregnant women should always consult first with a health care professional before taking any treatment.